Rosh Hashanah 2012

Rabbi Peter Schweitzer

This past June I visited Germany and Poland with my son Oren. I will be making a presentation about the trip at one of our Sunday adult study programs in October, but this morning I want to talk to you about a place we did not visit and how I had a realization that I was close to re-enacting a version of the Abraham and Isaac story that is traditionally read on Rosh Hashanah.

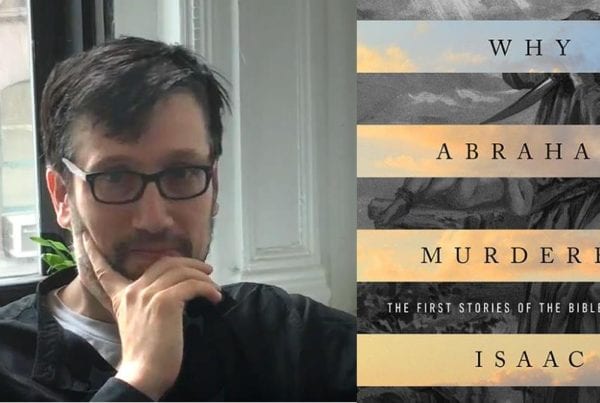

First a word about that story from Genesis. It has two names. One is the Test of Abraham and focuses on Abraham’s loyalty to God even to the point of obeying God’s command to sacrifice his beloved son Isaac. The story is also called The Binding of Isaac, which acknowledges Isaac’s role of victim, though in the rabbinic literature Isaac is complicit with Abraham and goes along without a protest. But perhaps the story ought to be called, The Insane Demands of a Cruel God and the Unconscionable Obedience of a Fanatical Unquestioning Believer. Or it ought to be simply called, The Traumatizing of Isaac and How He Ended up in Therapy for the Rest of His Life.

Now the one person that is conspicuously missing from the story and these various titles is Sarah, wife to the crazy man and mother to the poor shnook. Where was she? What did she know about the test? Did she go along with it? Or did she protest and Abraham went off anyway?

The rabbinic midrash is very telling on this matter. Abraham was quite aware that he could not tell Sarah the truth. She would stand in his way. So instead he tells her that it is time for Isaac to get educated and that the next morning he would take him to their version of boarding school where he would learn the ways of God. Sarah was reluctant to part with Isaac, but gave her blessing and at the same time implored Abraham to take good care of Isaac along the way. “If he is hungry, give him bread, and if he is thirsty, give him water to drink. Don’t let him sit in the sun too long, and don’t let him go off by himself.”

So now let me tell you about what we did not do in Germany. We did not visit a place called Sachsenhausen, which was a concentration camp about twenty miles outside of Berlin. But we almost did, until I changed my mind.

Now I had already seen three other concentration camps on earlier trips to Europe. When I was in college I visited Dachau, which is near Munich. In 1995, I went to Auschwitz. And more recently, in 2004, when we were in Prague with Rabbi Sherwin Wine, founder of our movement, we went to Theresienstadt. Oren was along for that trip, but he was only three and in a stroller, and couldn’t possibly understand what we were seeing.

Now each time I visited these concentration camps I understood the enormity of what had transpired in these hideous places, but it was remote to me personally. Only recently did I become aware of relatives who were among the six million who had perished.

But Sachsenhausen is different for me than all those other places. That’s because this is where my grandfather Hugo was imprisoned after he was arrested following Kristallnacht, the Night of Broken Glass, on November 8, 1938. I carry the middle name Hugh after him.

Thankfully, my grandfather was released several weeks later through the intervention of a Christian friend from his business. In fact, most of the Jews were soon released in exchange for a stated intent to emigrate. But even in this short time, the prisoners suffered greatly. My grandfather came home with internal bleeding that was probably the result of an ulcer and the gauntlet of beatings the prisoners experienced when they were arrested.

Then, in early 1939, my grandparents and my aunt, my father’s twin sister, were able to leave Germany for England. My father was already here in New York on his own since March of 1936.

My grandmother died in England during the war and my grandfather and aunt arrived here in 1946, but he died in 1950, two years before I was born. So Sachsenhausen meant something different to me and I had always wanted to visit in tribute to my grandfather who I never knew.

Last April, when I starting thinking about our trip to Germany, I arranged for a private tour guide who would show us around for a few days. One day would be for major sites like Checkpoint Charlie, the remnants of the Berlin Wall and the Jewish section in what was East Germany. Another day we would visit various places where my family lived including my father’s school and where his temple stood. I set up a third day to visit Sachsenhausen, but I didn’t tell Sarah – I mean, Myrna, my wife.

I knew fairly well – no, I knew exactly what she would say – but I didn’t say a word. At the same time, I became increasingly anxious about whether this was the right thing to do with a son who was just on the verge of turning eleven. At first I tried to rationalize it. After all, my grandfather was released. It was a story with a qualified happy ending, at least for us. The suffering he experienced might have shortened his life, but at least he survived and made it to this country.

Still, I was having trouble talking myself into it. I raised my concerns by email with our guide and she assured me that we could skip certain areas where the worst things happened, but in the end I didn’t see how that would be possible. I could imagine ourselves standing there while some tour group twenty feet away was being regaled with all the horrendous details that I wanted to avoid.

Finally, I listened to the better side of my conscience. I canceled our day trip to Sachsenhausen and I felt greatly relieved. For two reasons. First, because I knew that it was wrong to impose this trip on Oren when he was not ready for it yet. He ought to make that decision for himself. I had no right to bind him with my agenda.

And second, I was just as relieved – maybe even more? — that I wouldn’t have to tell Myrna where we had gone after the fact. “Oh, by the way, you’ll never guess what we did on the third day in Berlin.” Now I could have kept this whole to matter to myself, but it was important to still come clean. And so I shared this whole saga with her via this talk that she previewed.

Unlike Abraham, I caught myself in the nick of time. I canceled the order. I got hold of my better judgment. And I realized how easy it is to not think clearly and make poor decisions. Or how hard it is to change plans once they are underway. Because reversing course can feel embarrassing, like there is something wrong with changing our mind, even at the last minute. So some people take jobs they really don’t want. Or they go through with a marriage they really don’t feel is right, because somehow calling it off ahead of time feels worse.

Or, more mundanely but likely more often and just as consequential, I understand how hard it is to catch ourselves before uttering an unkind word, a sarcastic gibe, a hurtful comment that we could have self-censured.

I believe when this happens we not only bring pain to others, but we also bring sorrow to ourselves on account of our failings. We really want to do better. We really can do better. But we stumble along the way and the path is never smooth.

But rather than beat up on ourselves excessively for our human foibles, we believe in moving forward with new resolve to do better next time.

To become the Abraham that rejects the command.

To become the Isaac that doesn’t just go along for the ride.

To become the Sarah who will listen kindly and forgive our missteps.

To paraphase a line from the book of Psalms, “May the words of my mouth and the meditations of my heart, and the deeds of hands be thoughtful, caring and kind…to others…and to myself.”

Shana tovah.