The Passover Haggadah offers the traditional Exodus origin story basing itself on a rabbinic understanding of the Hebrew Bible.

One of the most powerful sayings in the Rabbinic compilations of Pirkei Avot is, “Know where you came from”.

But where did we come from? The Passover Haggadah offers the traditional Exodus origin story basing itself on a rabbinic understanding of the Hebrew Bible. This myth of Exodus and Return overseen by Moses is one of the central myths of Jewish peoplehood, and exerts an enormous force on our history and on our values to this very day, yet it is not the story as far as modern scholarship can ascertain.

So little of the Exodus myth is corroborated in any reliable historical sources. In fact, even the Bible itself offers several alternative stories of origin if we dig deep enough; here I only have space for one…

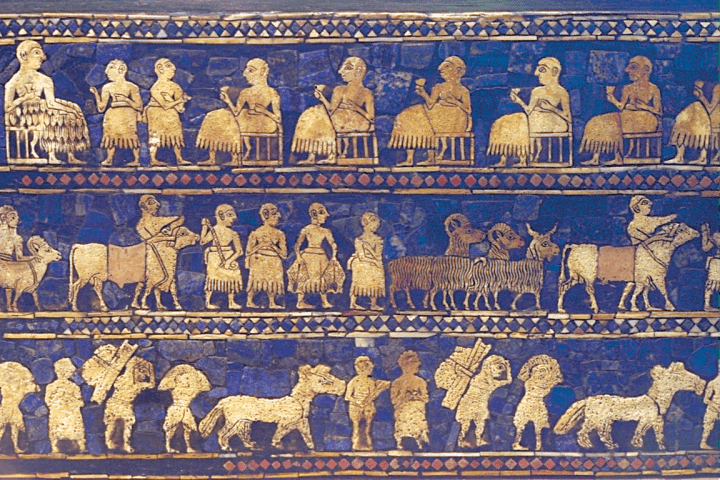

What if the Israelite ancestors, having come from Mesopotamia and or Syria, never leave. That’s right, they settled peacefully in Canaan and just slowly and gradually grew into a nation. In this version of events there is no Exodus because they never went to Egypt, nor is there an account of entrance into the land because they had already been there for so long.

The most intriguing clue to this version of our origin myth is found in a short story in I Chronicles 7:20-23: Instead of settling in Egypt because of a famine, Jacob’s great-grandchildren were rustling cattle in Philistia, just south of modern day Tel Aviv on the Mediterranean coast. They get caught in the act and are murdered and Ephraim, their father, mourns for them. In Canaan, not in Egypt. There are other mysterious biblical stories that corroborate this origin myth, but I do not have space for them here.

Absent further discoveries, there is no way to know which story of origin is correct, the violent Exodus, or this more benign story. What is important to acknowledge is the plurality of origin-myths in our most ancient piece of literature. It is not without reason that the Bible is referred to as the great justifier, but instead of wrestling with a problematic tradition when it doesn’t conform with our values, when it doesn’t say what we want it to say, why not pick up another strand of the tapestry and pull?

Rabbi Doctor Tzemah Yoreh