The following essay about children’s art was written by Jesse Robbins, a middle schooler, enrolled in City Congregation’s Bar/Bat Mitzvah program. Students spend a year and a half researching their heritage, values and beliefs, and write on a Jewish subject of their choice, their major project; an example of this last component can be seen below. The process improves both the student’s writing and critical thinking skills, as well as his/her self confidence and overall maturity.

Terezin, originally a vacation destination reserved for Czech nobility, became a ghetto after orders in 1940, by Nazi Germany. “Ghetto” is defined as a part of a city occupied by a minority group or a place where people are put to be restricted or isolated. It was here, that many Jews were held during WWII.

The Theresienstadt Ghetto, or Terezín Ghetto, is located 30 miles north of Prague in the Czech Republic and held more than 150,000 Jewish men, women, and children. It was mainly for Jews from Czechoslovakia, but also for those deported from Germany, Austria, the Netherlands, and Denmark. People were held captive for long periods of time before being sent to their deaths at concentration camps, primarily Treblinka and Auschwitz. There was extreme overcrowding and terrible conditions at Terezin. About 33,000 people died from disease and malnutrition. The dorms had so many people crammed in that each person had about 16 square feet to themselves. That’s about the size of two door frames.

In 1943, the International Red Cross was sent to Terezin for an inspection. There was a myth that Terezin was a Democratic Jewish Settlement. The public believed it was a place where Jews could live freely and self-govern. The Nazis made propaganda movies to show the world and The Red Cross that Terezin was not a prison. They were worried about how it appeared to the rest of the world and wanted them to see how well the Jewish people were living during the war. They did a massive clean-up of the camp, painted and landscaped, and in the end, it looked like a resort. Immediately before the inspection, many prisoners were sent to Auschwitz and Treblinka, where they were killed, to dispel the look of overcrowding. The Red Cross “reported favorably, commenting that the housing was airy and attractive, food was adequate, and medical supplies were sufficient” (p. 49, Terezin: Voices from the Holocaust, by Ruth Thomson).

But the truth about what was happening at Terezin was quite the opposite of what the Red Cross experienced. When families were transported there, they were immediately separated. Men in one area and women in another, also the children–boys and girls–lived in separate dorms. In their diaries, prisoners describe their daily life. Wake-up time was at 7 a.m. Morning was the worst for many since their dreams provided an escape from the reality they were living. After waking, the children were sent to the bathroom. There were only about two toilets for every 120 children, so they waited a long time in line. Every day was filled with work and chores, even for young children. The responsibilities included cooking, cleaning, and gardening. Food was mostly soup (water that either tasted slightly salty or slightly like coffee) and every few days a piece of bread was offered. It was never enough. Steven Frank, a Dutch schoolboy at Terezin said, “I heard some people trying to alleviate this ache (of hunger) by sucking their buttons, in the hope that would con the brain into believing they were actually eating something”. (Terezin, Voices from the Holocaust by Ruth Thomson, page 22) The Nazis knew they were starving the prisoners.

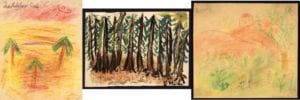

Inmates at Terezin included scholars, philosophers, scientists, musicians, artists, and children. In fact, over 15,000 of the residents of the Terezín Ghetto were children. Friedl Dicker-Brandeis was an artist and educator imprisoned at Terezin. She taught drawing classes to the children in secret. The paper they used in their art classes was scavenged from the garbage and the covering of old packages. Dicker-Brandeis said her objective in teaching the kids art was not to create artists, but to “develop their creative, emotional, and social intellect” (Terezin Voices from the Holocaust. Ruth Thomson). She allowed the kids to express themselves and tap into their fantasies and emotions. She sometimes offered them a prompt, “Paint the place where you wish you were now or paint what you wish for”. This had a therapeutic effect on the kids and taught them to cope with their oppression by expressing their feelings through art. Many prisoners enjoyed art classes simply for the reason of self-enjoyment and self-expression. Helga Pollak, a Czech teenager who was imprisoned at Terezin and survived, said of Dicker-Brandeis, “There was something about her way of teaching that made us, for the moment, feel free of care” (p.41, Terezin: Voices from the Holocaust).

Each of these 3 pictures all include a sun. I imagine Dicker-Brandeis gave a prompt to draw nature or trees and each of these feel hopeful and full of life to me. The sun makes me think of light and warmth, just the opposite of what these children were living.

Another student, Raja, remembered Mrs. Brandeis “as a tender, highly intelligent woman who managed–for some hours every week–to create a fairy world for us in Terezin…a world that made us forget all the surrounding hardships that were not spared despite our young ages” (p. ix…I never saw another butterfly…)

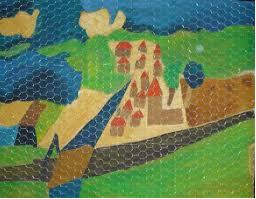

by Hanus Weinberg, born August 18, 1931. Deported to Terezin December 5, 1942. The theme of this picture was suggested by Dicker Brandeis, A View of Terezin. He perished in Auschwitz December 15, 1943. To me this picture might have been from his imagination of what Terezin looked like before it was a ghetto. It’s bright and lush.

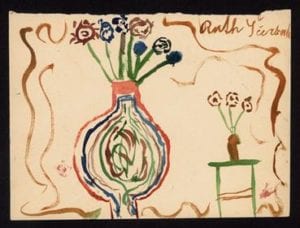

Dicker-Brandeis taught the children the way she had been taught: through “exercises in breathing and rhythm; the study of reproductions, texture, color values; the importance of observation, patience; the freeing of oneself from the outer world of numbing routine and the inner world of dread” (p. xx…I never saw another butterfly…). The children painted and drew flowers, butterflies, animals, cities, storms, family pictures, holidays. They portrayed their inner thoughts and “tortured emotions,” which Dicker-Brandeis was “able to enter and try and heal.”

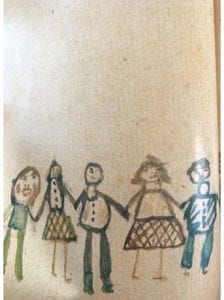

We know now that art therapy allows people a way of expressing themselves through painting or drawing. By looking at the pictures created by the children from Terezin, we can sense different messages or symbols to help us better understand what they were feeling and experiencing. In many of the pictures, children draw themselves holding hands with others or with their families. I imagine it must have been so hard to be separated from their parents, family and everything they once knew.

Common themes seen in the children’s artwork are returning home, misery of experience, food, family and freedom, intense feelings of claustrophobia, a sense of the fragility of one’s physical existence, and the lack of human value of the camp inmates (psychological study from Oxford by, Frances Gaezer Grossman, in 1989). Prisoners were crowded in small spaces, in inhumane circumstances.

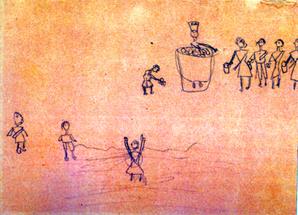

Everyone was Hungry, L.Franklova, 10 years old, born in Brno, January 12, 1931 and deported to Terezin December 5, 1941. There are about 19 of her drawings in the found collection. She was there until 1944. She was killed in Auschwitz October 19, 1944. It seems like this picture represented the artist’s experience of what was going on at the time. The top portion of the picture shows prisoners in line being served food. The bottom of the picture appears to show a prisoner getting shot and maybe one running away. This shows how close life and death were related for the prisoners and how death was not as feared as one might think in life outside the prison.

Hana Zieglerová (Hana Zieglerová 1933-1944). The black smoke coming out of the chimney is gloomy, but the trees flowering is hopeful.

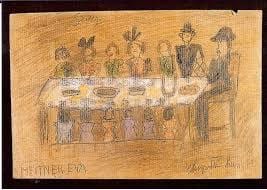

Passover Seder, Eva Meitnerova, born May 1, 1928 and killed on November 28, 1944. I think this was a happy memory for the artist, somewhere she wished she could go back to.

I chose these pictures because they are a good representation of the vast experiences and atrocities that the prisoners faced. I was struck by the emotion that was conveyed through the children’s artwork, like hope and sadness, and by the way the children represented their memories of the past and fantasies about where they wished they were.

Dicker-Brandeis collected the artwork and kept it in two suitcases, which she hid in the Ghetto’s children’s dormitory. In 1944, she, along with many of the children, was transported to Auschwitz, where they were killed. After the liberation of the Ghetto on May 8, 1945, the drawings were retrieved by Raja Englanderova, a former student of Friedl Dicker-Brandeis. She gave them to Willy Groag, a liberated prisoner from Terezin, and he passed them on to the Jewish Museum in Prague. Today some of these works are in Prague, Israel, and the Holocaust Museum in Washington, D.C. There were over 4,500 pieces of art recovered. Less than 150 children out of 15,000 survived Terezin, and no one under the age of 14.

These drawings appear on the surface to be simple children’s art work, just like the ones I used to draw myself when I was young. However, now–knowing the history and context of this art, who drew it, when and where–changed how I see them, how I feel about them and what I’ve learned about this time in history. It is anything but “typical” children’s art. Kids often draw flowers and suns and pictures of their families, but they come from such a different place. The artwork found at Terezin documents a specific time in history and tells a horrific story. I look forward to seeing this art in different museums as well as visiting Terezin in person one day. The artwork will always remind viewers to never forget.