The Jewish calendar generally associates spring with the holiday of Passover, but since the calendar fluctuates with the tides of the moon, this year the beginning of spring coincides with Purim, that most enigmatic of holidays. Purim really has nothing to do with the natural world or the spring, and the only flora in the book of Esther is the tall tree upon which Haman is hung.

As a free-thinker I guess I am supposed to appreciate the holiday of Purim and its central text, the book of Esther, which is completely devoid of any mention of God. But how deeply can I valorize any book which blithely kills 75,000 non-Jews as an act of retribution, or that celebrates forced conversion?! At one level that is exactly what the book demands, for us to take it less than seriously. The characters are caricatures, King Achashverosh is the classic buffoon, Esther is the beautiful princess, and you can almost see Haman’s sinister mustache.

At another level, though, this book is among the most deeply heretical in the Jewish canon, for the struggle at its center is a struggle between heathen gods, and that is why I love it. The Jewish Esther is a thinly veiled representation of the goddess Ishtar, the powerful Assyrian goddess of fertility, and Moredecai, her uncle, represents the Babylonian King of the Gods, Marduk. Haman could represent Ahriman, the spirit of darkness in Zoroastrian mythology. The Babylonian gods Marduk and Ishtar defeat the Persian gods in the book of Esther, which is not exactly how it transpired historically, but that doesn’t particularly matter. One of the ways we as cultural Jews can celebrate our holidays is by a renewed appreciation of our wondrously diverse literary canon, and so I raise my glass to the author of the book of Esther and say, L’chaim and thank you!

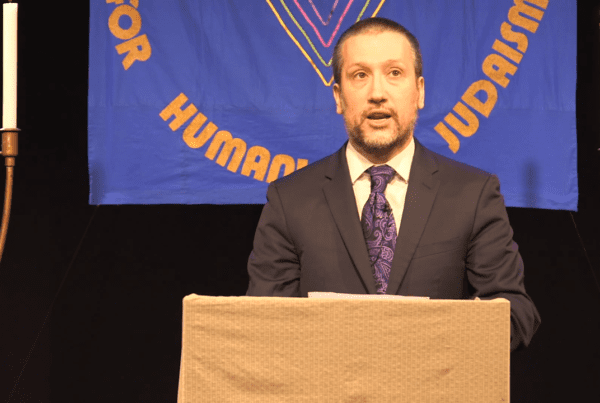

Rabbi Tzemah Yoreh