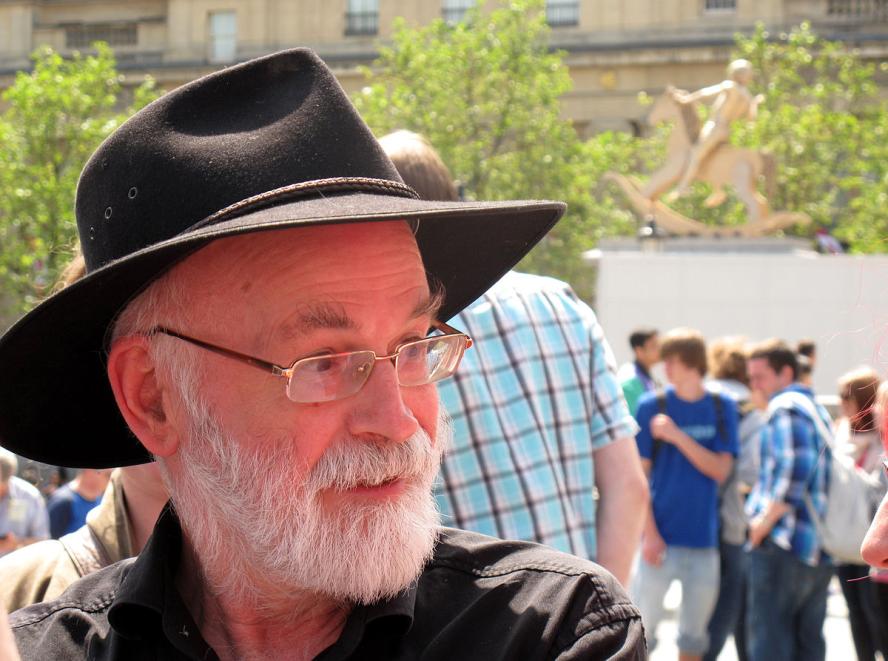

On November 13th, 2020, we had the honor and pleasure of having a few of our members share stories about author Sir Terry Pratchett, and how he changed their lives. Danny Karni, Jim Ryan, and Rabbi Tzemah Yoreh gave us permission to share their talks.

This event was a part of our program series, “My Humanistic Author”, in which members share how a creator – author, director, artist, poet, etc. – made a significant Humanistic impact on their lives. If you are a member and would like to share a story of a creator who changed your life, please contact the shabbat committee.

Danny Karni talked about the Humanism of Terry Pratchett as reflected in his Discworld series, the text of his talk is posted below.

Jim Ryan talked about the author’s attitude towards death, as reflected in the character of Death. His recording is posted below.

Rabbi Tzemah Yoreh spoke about the book Small Gods and its relevance to modern religious thought. His recording is posted below.

Watch a recording of Jim Ryan and Rabbi Tzemah’s presentations:

Read Danny’s presentation:

Sir Terry Pratchett is a big part of why I consider myself a Humanist. He hardly ever used the term in his books that I’ve read, but his writing is laced with humanistic ideas. I hope to demonstrate this and motivate you to pick up this series or continue reading it if you’ve started but haven’t gotten to the really good bits yet.

If you’re not familiar with the Discworld series, here’s an adapted quote from Sir Terry himself:

“Discworld was conceived as the antidote to fantasy stories. On the surface it’s your consensus fantasy universe, you know the one with the trolls and the vampires and the elves and everything except that it’s taken seriously. If you take it seriously it becomes funny.

A lot of the books are set in the city of Ankh-Morpork, which is kind of a cross between Tudor London and modern New York. There are trolls, dwarves and vampires and everyone’s there to make a buck.

The concerns are often quite modern, set against a background which will remind you of a lot of fantasy stories.”

Beginning as a parody, evolving into satire

The Discworld starts out as a parody, where applying our world – “roundworld” – concepts like tourism, insurance and economics to a fantasy setting is the main driver for comedy.

With the introduction of some recurring characters, Pratchett starts exploring how people in positions of power can use their power for good and bad. He does this best by shifting from parody to satire, still referencing roundworld concepts, but contextualizing them differently, constructing situations that allow his characters to explore choice, self determination, truth, duty and other philosophical questions. Sometimes there are no simple answers, sometimes there are, as in this following dialogue:

“Sin, young man, is when you treat people like things. Including yourself. That’s what sin is.”

“It’s a lot more complicated than that–“

“No. It ain’t. When people say things are a lot more complicated than that, they means they’re getting worried that they won’t like the truth. People as things, that’s where it starts.”

“Oh, I’m sure there are worse crimes–“

“But they starts with thinking about people as things…”

His repeated revisits to characters and settings allow him to create characters that are complex and well-rounded. Even minor characters who started as caricatures are often humanized, not by exposing some past trauma that “made them bad”, but just by… living. He does this with people from all walks of life, aloof kings and unhoused people at the edges of society alike. Heck, this extends to mythical creatures such as dwarfs, trolls, zombies, vampires, and even golems.

Generally speaking, Sir Terry always had a knack for the dynamics of power. He demonstrates how good people can really only accomplish great things when working together with others, as journalists, activists, public servants etc. In fact, despite his books being full of Great Men (later the balance shifts to mostly Great Women) his writing is still a clear rejection of Great Man History. Arcs of social progress span across multiple books and have to do with gradual cultural shifts. The really significant changes to everyday life come with the advent of transit, mass media and communication. The great city of Ankh-Morpork goes from a smelly, cutthroat city, full of economic disparity to the place people flock to from all over the disc thanks to its multiculturalism, booming industry and tolerant atmosphere despite it still being a smelly, cutthroat city, full of economic disparity. This was not all thanks to its benevolent tyrant, Lord Vetinari, he worked with many others to let the city transform itself.

A key part to this is the city guard. It is transformed from the only place who would hire the no goodniks who were rejected even by the thieves guild, to a modern, regulated police force. This is not done by purging all the bad apples, but instead instituting a new culture of oversight and commitment to the public good, while understanding that no community can be policed without its consent.

This is done under the leadership of Samuel Vimes, who perceives the place of police in society thusly:

“It always embarrassed Samuel Vimes when civilians tried to speak to him in what they thought was ‘policeman’. If it came to that, he hated thinking of them as civilians. What was a policeman, if not a civilian with a uniform and a badge? But they tended to use the term these days as a way of describing people who were not policemen. It was a dangerous habit: once policemen stopped being civilians the only other thing they could be was soldiers. “ — from Snuff by Terry Pratchett

This point of view that centers systems paves the way for Pratchett to start exploring not just relationships between individual characters, but often goes up to the geopolitical realm. We get to see how nationalism, colonialism, bigotry and economic inequality impact the different kingdoms, city states and other political players on the disc. Even then, Sir Terry sees how people of different cultures and backgrounds have a lot in common.

For example, In the book Jingo, The lost city of Leshp has just surfaced in the circle sea and both people from the city and neighboring Klatch (a stand in for arab or middle eastern cultures) scramble to pick it apart for valuables:

“Why are our people going out there,” said Mr. Boggis of the Thieves’ Guild.

“Because they are showing a brisk pioneering spirit and seeking wealth and … additional wealth in a new land,” said Lord Vetinari.

“What’s in it for the Klatchians?” said Lord Downey.

“Oh, they’ve gone out there because they are a bunch of unprincipled opportunists always ready to grab something for nothing,” said Lord Vetinari.

“A mastery summation, if I may say so, my lord,” said Mr. Burleigh.

The Patrician looked down again at his notes. “Oh, I do beg your pardon, I seem to have read those last two sentences in the wrong order…”

This acknowledgement that nationalism and xenophobia look very similar in cultures that are in conflict serves to paint such amorphous groups as “nations” or “cultures” as made of individual people, who can be driven by emotions or by rational thought, and point at how no culture is immune to propaganda that panders to them.

Acknowledging the slow progress of history doesn’t excuse individuals from doing the right thing:

‘… I dearly wished I could change the past. Well, I can’t, but I can change the present, so that when it becomes the past it will turn out to be a past worth having.’

This is reminiscent of the Rabbi Tarfon quote, “The task is not yours to complete, nor are you free to desist from it”.

This is not to say that he or the series are without fault. This progression isn’t linear, it has its ups and downs, bullseyes and misses. I’m comforted to find that most of Pratchett missteps are often corrected later in the series. Where one book might express unabashed orientalism, many others deliberately humanize foreign people with odd and unrelatable cultural practices.

This is a good role model for a humanist worldview: we make mistakes and have to unlearn misconceptions and stereotypes, bigotry we may even not realize we have. The important thing is not to never make mistakes, but to keep working at doing better.

Whatever hardship and turmoil his stories sometimes hold, which include wars, revolutions, petty meddling gods, and the occasional lovecraftian monster, Sir Terry’s was a hopeless optimist, or actually, a quite hopeful optimist!

While no book ends with the abolishment of any of these difficult phenomena, realistically, they often end with some improvement to the overall conditions, and always have good endings. They are an uplifting and inspiring read.

To see upcoming events or watch them live, check out our calendar