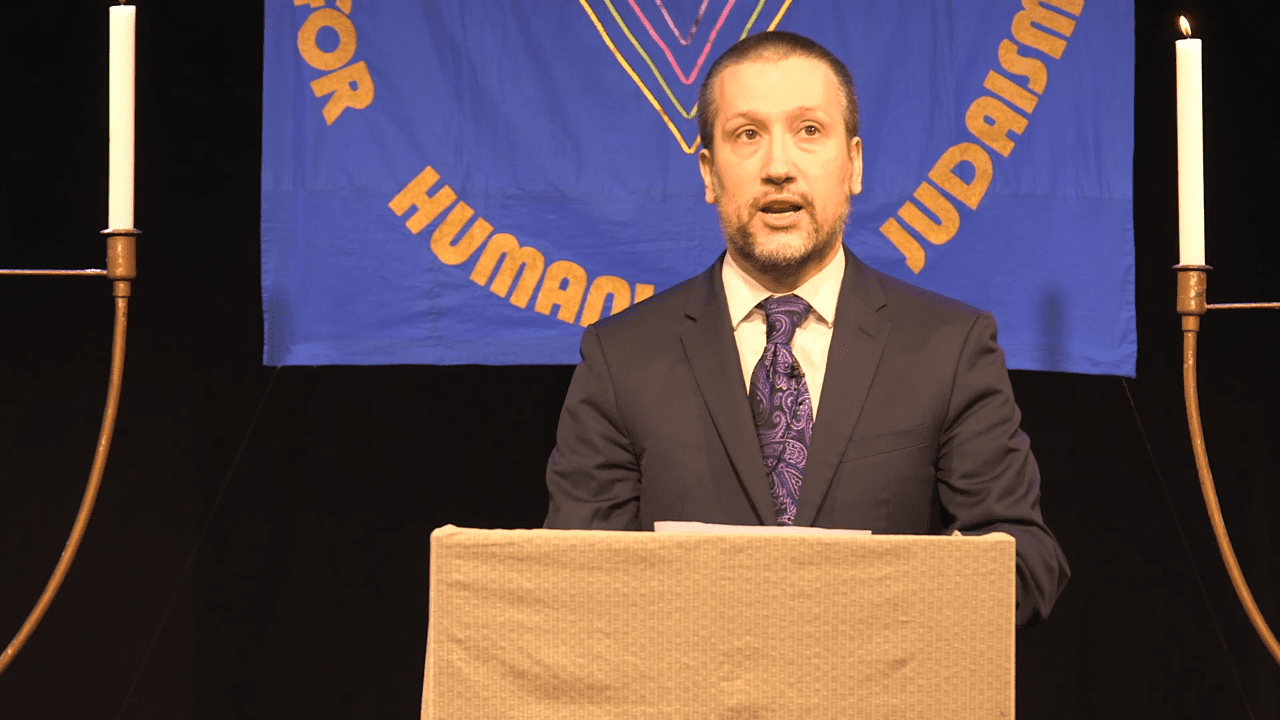

During the Kol Nidre service, Rabbi Tzemah gave this sermon. Watch the video or read the transcript below.

Watch a recording of the sermon:

RUTH

Kol Nidrei is usually a time to look at your commitments and see how you may need to adjust them.

It is a time for renewal and rejuvenation, a time for promising to improve. But we are in the midst of a storm. The coronavirus rages unabated, and a seemingly endless deluge of horrific incidents of racial injustice and protest wrack our cities. A storm can wash away detritus and bring freshness into the world but we must wait for that; right now, we are in the middle of it.

In the midst of a storm we seek refuge.

My refuge has been for many years the great works of world literature. And one of the dearest works for me has been the book of Ruth in the Hebrew Bible. It is a book about how love and compassion overcome privilege and prejudice, and change a system for the better. And though traditionally it is read on Shavuot, it is a story for our time, and now more poignantly than I thought possible, since our own Ruth, Ruth Bader Ginsburg died 9 days ago.

For those of you who are familiar with this gem of a story bear with me, I will tell it through somewhat of a different lens.

The story is set at a time of horrible famine; people are forced to relocate or starve, and the family of Naomi find themselves foreign refugees in the land of Moab. Moabites are often the enemies of the Israelites, so this relocation is not without its perils. They find haven and welcome in Moab, and Naomi’s sons intermarry with Moabite women, though this is entirely prohibited according to the Torah. Then disaster strikes again and Naomi’s husband and sons die. Naomi is now alone in the world, without the status and security that family gives her, without the privilege of being a native Moabite. This is especially horrendous for Naomi who is elderly cannot support herself. The one glimmer of positive news is that the famine is finally over in Judea and she can go home.

She starts the long journey back to Judea, an old and broken woman, but lo, with her come her two erstwhile daughters-in-law offering what they can in support.

She pleads with them to leave three times. One of her daughters-in-law accedes and turns her back, returning to Moab. Ruth does not. She vows, ‘Wherever you shall go, I shall go too, wherever you sleep, I shall sleep, your people is my people, your god is my god. Wherever you die I shall die too and there I shall be buried. So help me God, only death will separate us”.

Naomi lets her come.

Love bridges all divides. And thus, just like Naomi, Ruth becomes a refugee from her homeland, forsaking all privilege and safety to help another person.

In Judea, it is the time of reaping barley, and Ruth who is yet young gathers sheaves at the edges of the fields, and follows the reapers, gathering what they drop. She doesn’t know it, but by chance she finds herself in the field of Boaz, a distant relative of Naomi’s. Ruth is a foreign woman alone, she speaks a foreign language, and risks abuse, but she needs to feed her mother-in-law.

Boaz finds out who Ruth is, and in an outpouring of compassion comes to her and says, ‘I have been told of all you did for your mother-in-law after the death of your husband, how you went to a foreign land where you knew no one. May you be granted proper recompense for your great act of compassion’. This statement comes from a male with the greatest status and privilege in the city of Bethlehem, a man of property, a member of the tribe of Judah, the prince of tribes. Ruth lacks all status, all privilege, and all advantage, and yet Boaz speaks to Ruth as an equal, recognizing her for the greatness of her act, creating a bridge of compassion extended from Boaz to Ruth. But a bridge requires two sides.

Ruth recognizes the bridge that Boaz creates, and extends her own bridge to meet him. For though she lacks privilege and status in her new homeland, in the most important way they are equals; they are both compassionate human beings. Making herself completely vulnerable she walks on her bridge and meets Boaz in the field at night, and asks him to spread his mantle over her in protection and embrace. Boaz accepts. There are a few more twists to this story, but in the end Boaz and Ruth marry extralegally and Ruth gives birth to a child, who Naomi fosters, and who we are made to understand is the ancestor of King David.

This story will always demonstrate to me most poignantly that systemic privileges, societal status, and social class, even legal norms, can always be bridged with love and compassion. And when they are, something wonderful is brought into the world. We just need to reach out. That is why my eldest son is named Boaz.

In our wracked and riven country, the bridges of compassion and forgiveness are created every day by people thrust into the spotlight because their dearest ones have been killed or grievously injured.

David Whitley an Orlando Sentinel reporter remarked:

“A great irony of protesting is how the people who most deserve to get angry are often the voices of reason. The depressing part is how their pleas are routinely ignored.”

Julia Jackson, the mother of Jacob Blake, called out:

“To all police officers…I pray for you…everybody let’s use our hearts and intelligence to work together to show the world how humans are supposed to treat each other.”

And to protestors, “Please don’t burn up property and cause havoc and tear your own homes down in my son’s name.”

I fervently hope that her call, and the call of so many compassionate people seeking to bring peace, is heeded.

So, as we seek a haven in the storms that beset this year, please know that we can bridge these divides between us, even if it seems entirely unlikely. I believe this to be true.

Shanah Tova!

To see upcoming events or watch them live, check out our calendar